As a manuscript blossoms into a book, along the way, it’s scrutinized by numerous editors. Each different type of editor performs a discrete job, with some overlap that adds to efficiencies. They also share a goal: to make every book its best.

Line editing

A line editor examines a manuscript at a sentence level. And while they may mark up a manuscript similarly to a copy editor (see below), the line editor isn’t only looking for punctuation, spelling or grammatical errors.

They are focused on content, and how effectively the writer’s intended meaning is being conveyed. They may suggest rewording or restructuring sentences. Queries and questions are marked in the margins. At a basic level, the line editor seeks a seamless read.

The goal is to make an author’s voice clearly heard, but to avoid going too far and altering a writer’s style.

Developmental editing

Sometimes a writer believes they need only a line edit when they really need more than that. The developmental edit, or conceptual edit, analyzes the big picture. Is this plot working? Is the book properly organized?

Here we enter the intimate territory of the author-editor relationship. This is when the author gets their editorial letter.

The editor is now elbow-deep in the plot, and may request radical surgery: “Given Jane’s history with her father, does it make sense that she would leave now?” Or “You might consider cutting this prologue, and instead begin with the central character.” Maybe: “Your reader might appreciate a new scene here, complete with dialogue explaining the characters’ conflicting views.”

A developmental editor can be deeply involved in molding a plotline. This is editing at a macro level.

This type of editor works with the author to communicate the author’s vision. Concurrently, a likely goal—particularly if the editor is employed at a publishing house—is to optimize a book’s commercial qualities. A skillful editor working with a willing author can merge these interests, creating a smooth read with great sales potential.

Copy editing

This is what many people think of when they imagine what an editor does: a copy editor marks up a manuscript, correcting punctuation, and fixing spelling and grammar. At a publishing house, a thorough review by a copy editor is one of the first steps for a manuscript after being transmitted to the Production Department.

A sentence that ain’t so good becomes a sentence that is much better.

A copy editor is by definition efficient, so in addition to their many fixes, they mark up a manuscript with queries about the particulars, for example, “Is Lake Philip really so close to the Canadian border?” They want to keep the details and facts straight so readers don’t lose faith in the narrative: “But earlier in the text you wrote that Lola had shoulder length red hair. Want to change here (or earlier) for consistency?” Countless writers have sighed in relief when a scrupulous copy editor caught an overlooked goof.

Proofreading

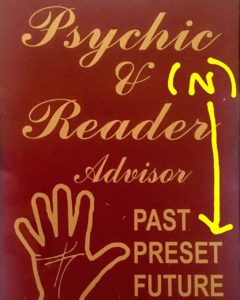

Everyone needs an editor.

Last but not least comes the proofreader, checking galleys or books in their final stages for remaining errors. Typos—or repeated text—may have sneaked into the book file, which a proofreader will note, but they may also return to the C.E.’s persnickety ways.

The novels of one bestselling writer I worked with invariably included numerous scenes of his main character driving around L.A. A greatly devoted proofreader always returned these manuscripts with plentiful queries about the highways and routes taken—a literary GPS, as it were. This author was eternally grateful—of course, in L.A., everyone enjoys an excuse to discuss more about traffic and the best possible route.

A collaborative effort

If the book publishing system is working at its best, career authors have full confidence in their editors’ capabilities and vice versa. When writers and editors share a vision, literary magic can happen.

How much editing is just right? Or too much? How do you know which of the types of editors you need? Share your experience with us on Facebook.