Editorial jobs in publishing houses are often difficult, demanding, and ill-paid. They can also be challenging, satisfying, and inspirational—a total blast. Who cares if you’re paid peanuts, if you get free drinks and real peanuts at book parties filled with fascinating people of all sorts? In short, being an editor is the world’s best job for bookworms with no other apparent skills. A great perk of publishing jobs is one’s passionate, devoted and fascinating colleagues. A fledgling editor learns skills on the fly, so generous mentors can be key.

“Almost there, but…”

Bob Loomis started off at Random House working for the eminent Bennett Cerf. Bob stayed at the company over fifty years, and while I was there it was my privilege to work on a number of projects alongside this erudite, funny man.

A raconteur of note, Bob shared with me countless stories of literary legends present and past, jaw-dropping tales of misbehavior and scandal. ~heaven~

My favorite editorial project with Bob may have been our work together on Too Brief a Treat: The Letters of Truman Capote. Upon combing through (and trimming) this sizeable collection of mesmerizing correspondence, a reference was noted of an unpublished Capote short story, supposedly filed away in the New York Public Library on 42nd Street. “The Bargain” was subsequently found and published in The New York Times Book Review, as well as in a Capote short story collection published by Random House. This was book publishing at its most exhilarating.

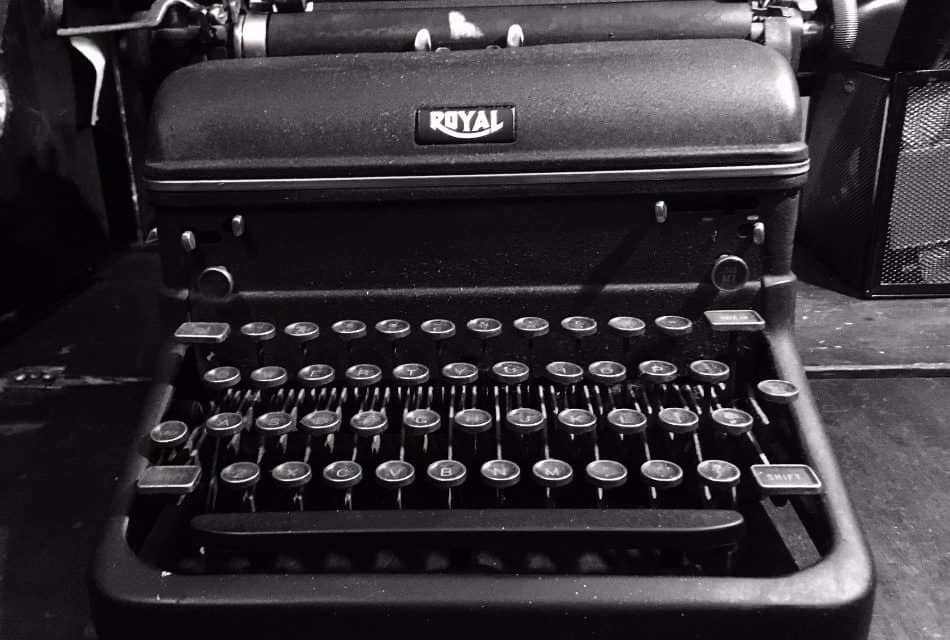

When Bob Loomis retired, he gave me his Royal typewriter, which I treasure. I love just looking at it, and imagining its keys tapping editorial letters to Maya Angelou, Bill Styron or Jerzy Kosinski. Bob was an old-school editor, a gentleman. His editorial technique was quietly straightforward (penciling in “We know” on a manuscript), and he improved my manners when writing editorial letters. To an author with much work still to do, Bob might declare their manuscript wonderful, but would then diplomatically add, “We’re almost there but not quite,” or “This may yet need a bit more polishing.” Clear directions on how to accomplish these improvements would follow with consummate politesse.

The hidden gem

An editor’s skill may not only be on the page. A highly successful editor’s greatest talent may be their discerning eye: the ability to spot a best seller. In Michael Korda’s publishing memoir Another Life he recounts his literary adventures with numerous egocentric, childish and alcoholic mega-selling authors (Jacqueline Susann, Harold Robbins, to name two) whom it seems Korda was responsible for making famous. Hundreds of juicy pages chronicle the embarrassing gaffes this publishing veteran protects his authors from, the overhauls of their manuscripts and his cliffhanging saves. In Korda’s telling, these writers seemed fortunate to have had him there to rescue them. And I suppose it cannot be denied that some authors do need to be saved from themselves. The objective eye of an experienced editor may do just that. In truth, there are few situations where we couldn’t all use sensible guidance.

Where others might overlook it, the best editors spot the buried gem buried in the soul-annihilating submission pile.

Korda had a great eye for what worked. Just ask one of his biggest fans, the charming and prolific best-selling mystery writer Mary Higgins Clark.

Behind the curtain

If literary hero Michael does not stress that an editor’s best work is behind the scenes, that was certainly the clear preference of legendary editor-of-editors Maxwell Perkins. He wrote that if children should be seen and not heard, an editor should not even be seen.

Perkins felt an editor should be “a skilled objective outsider,” but an editor’s relationship with their author can sometimes morph into therapist, friend, or even enemy. Maxwell Perkins not only doled out wisdom on prose. He once paid veterinary bills for one of his author’s cats.

Making what’s good better

But back to literary advice. The goal in effective editorial letters is to inspire a writer’s best, to bring forth their story’s strengths while simultaneously addressing issues that could potentially impede readership. Editors do not impose their views but bring the authors’ ideas to the fore. When encountering a problem, suggestions as to how to solve it may be offered by a helpful editor. Whether these suggestions are taken up is of no consequence. Writers should address their glitches as they see fit; as long as an author’s fix works, all is well. Maxwell Perkins went further, even encouraging writer rebellion, telling F. Scott Fitzgerald, “Do not ever defer to my judgment.” Well, I suppose you must give writers their head, but I wouldn’t want to go that far.

The most skilled editors listen, empathize, and guide sensitive writers to make their book the best it can be. Readers around the world are grateful.

Have stories of your own to add? Join our Facebook discussion.