When you write, you lay out a line of words. The line of words is a miner’s pick, a woodcarver’s gouge, a surgeon’s probe. You wield it, and it digs a path you follow.

—Annie Dillard

If the sentences aren’t right, the story doesn’t matter. Sentences are the bricks with which we build our stories, line by line. Writing powerful sentences is key to writing powerful stories. That’s why editors are quick to reject manuscripts that lack what they call “sentence quality”—editor speak for good sentences. A good story just isn’t good enough unless it’s written in good sentences.

This may seem obvious, but I meet many writers who are unwilling to polish polish polish their prose. They’ve written the story, they think the writing’s fine, they want to get on with selling it. This can be especially true of those writing genre fiction, who believe—falsely—that the quality of the actual writing doesn’t matter so much as long as they are telling a good story. I was reminded of this recently as I read Andy Martin’s Reacher Said Nothing, in which Martin observes Lee Child as he writes Make Me, the 20th novel in his bestselling Jack Reacher series. Martin shows Lee Child worrying over his sentences the way mothers worry over their newborns.

You can learn to worry over your sentences—if you don’t already—with these tricks:

1. Read your work out loud.

This will help you develop your writer’s ear, your innate sense of voice and tone and rhythm that you’ve been developing ever since you learned to speak and to listen, to read and to write. You can hear it in other people’s work. Now you need to learn to hear it in your own.

1A. Better yet, have other people read it out loud.

Hear where they stumble, where they slow down, where they sail along.

Note: If you’ve been published, and your work is available on audio, listen to it. You’ll hear all kinds of things as you listen, both good and bad, especially if someone else is doing the narration. I confess that I refused to listen to my debut mystery A Borrowing of Bones for a long time. I was worried that it would be a slow form of Chinese water torture, listening to my ill-chosen words drip drip drip for 400 pages. Finally, I did, and while I did occasionally wince, I loved Kathleen McInerney’s narration. And I could hear my sentences in action, for better or worse.

2. Read like a writer.

Pay attention to the language, delight in superlative sentences, tap along to the rhythm, note the beat and the heat, the warp and the weft, the push and the pull of your favorite writers’ prose. Often this means reading the book twice—once to see what happens, and again to see the sentences.

3. Collect sentences.

Keep a Sentence Notebook where you write out great sentences as you come across them. And no, I don’t mean cutting and pasting them into a file, I mean physically writing them down, with pen and paper. This is good for your writer’s brain; you’ll learn more. (If you don’t believe me, maybe you’ll believe this study published in Scientific American.)

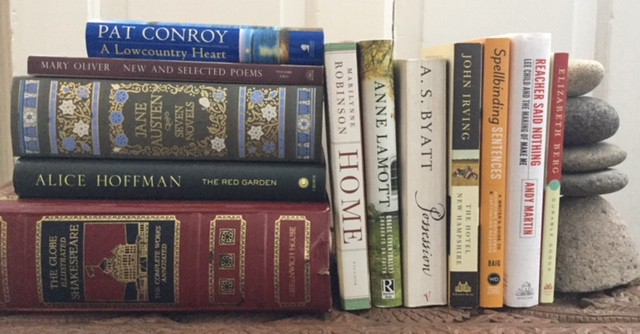

In mine, I have sentences from writers as different as Alice Hoffman, Pat Conroy, Marilynne Robinson, Shakespeare, Annie Lamott, Emerson, Mark Nepo, Elizabeth Berg, Thoreau, Lee Child, Louise Penny, Jane Austen, John Irving, and A.S. Byatt.

4. Read poetry.

Poetry is all about the power of language. Good poetry packs a punch, an emotional wallop delivered in dynamic prose. From the deep Zen of Basho to the wild exuberance of Whitman—and everything in between. Nothing teaches you more about the guts and grandeur of language than poetry. I read poetry because it reminds me what words and phrases and sentences are all about. The list of great poets is endless, I leave you to discover your favorites on your own. That said, if you think you don’t like poetry, try Mary Oliver.

5. Practice writing good sentences.

There are a lot of great resources to help you learn how to hone your sentences. These classics all belong on every writer’s shelf:

- Reacher Said Nothing, by Andy Martin (Bantam, 2015)

- The Elements of Style, by William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White (There are newer versions, but the Strunk and White edition is the classic.)

- Spellbinding Sentences, by Barbara Baig (Writers Digest Books, 2015)

- On Writing Well, 30th Anniversary Edition, by William Zinsser (Harper Perennial, 2012)

- How to Write a Sentence, by Stanley Fish (Harper, Reprint Edition, 2012)

- It Was the Best of Sentences, It Was the Worst of Sentences, by June Casagrande (Ten Speed Press, 2010)

For more on sentence quality, talk to us on Facebook.