Our ancestors told stories. Illustrated stories, as in these incredible Lascaux cave paintings. But all those thousands of years ago, there was no sense of a society that had gone before. These were the first storytellers and they had no reference other than the here and now.

We don’t have it that easy.

If you’re tempted to give up on achieving historical accuracy, it would be understandable. Writers of historical fiction can never get it truly right. The past is filled with people so different from us that it’s impossible to get into their skin and accurately tell a story through their eyes.

In his famous essay History and National Stupidity, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. said:

…the past is a chaos of events and personalities into which we cannot penetrate. It is beyond retrieval and it is beyond reconstruction. All historians know this in their souls.

In 1940, only 45% of houses in the United States had indoor plumbing. Travel was a luxury of the rich. Public education was limited and simplistic by today’s standards. Heart surgery was unknown; the very idea feared by surgeons. The list can go on for the 1940s or any other era, showing all the ways in which people then were different from those of us in the 21st Century. How important is any one factor? Perhaps not critically, but when you add them all up they build an image of people who are distinctly different from us—they react differently, think differently, act differently.

Historical fiction is often defined as a work of fiction written fifty years or more after the events described.

But if you’re going to persevere? And succeed? The first step is to acknowledge the deep differences that separate us from characters in historical fiction.

Decide how and when your characters live

The first step is to acknowledge the deep differences that separate us from characters in historical fiction.

Make your own list of ways in which people during your historical period are different. Think about the influences that formed them and inform their decisions. Keep the list near you and add to it as you do your research. A psychic image will emerge, one which will be quite different from a modern person dressed in ancient garb.

Decide where your characters live

A travel book published around the time of your story will be invaluable in recreating a setting in terms of time and place. Any time you find one of these in a used book sale or online, grab it.

Contemporary maps do the same thing, giving you the confidence to chart out a course in town or country that will be true to the times. The same goes for contemporary novels or nonfiction. Let’s say you’re writing a seafaring novel in the late 19th Century. Find novels based on sea voyages written during that period to learn how people in those days experienced a nautical adventure.

I recently stumbled across the Green Books. These were annual guides for the Negro Motorist, published from 1936 to 1966. In the era of Jim Crow, these books offered advice about safe places to stop, eat, and stay, as well as locations to avoid. As stated on the cover, Carry your Green Book with you…you may need it. These books describe an American environment hidden from many people.

Immerse yourself

Read everything about your time period. Watch films that relate to your setting. Go to a museum and view contemporary artwork. Listen to the music your characters would have heard. Travel if you can but do everything possible to immerse yourself in their sense of time and place. I call it my theory of total immersion.

Know when to stop

I don’t mean stop the research. I mean: don’t go beyond your timeline. In the NOW of your story, no one knows what is going to happen next. Make believe you don’t either. When I was researching WWII in the South Pacific for The White Ghost, I stopped reading accounts of those battles after August 1943. My characters didn’t know how it would all end, so why should I?

In sum, your history homework assignment is: Immerse yourself.

There’s only one caution.

Don’t write about most of it

Total immersion is a way to make historical fiction faithful to the era about which you’re writing. If you follow this practice, absorbing everything you can through any medium you find, you’re well on your way.

But then follow Ernest Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory. Here’s how Hemingway defined it:

If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.

In his short story “Big Two-Hearted River,” Hemingway was writing about the Great War and his experiences in it, but the war is never mentioned. Instead, his protagonist Nick Adams arrives at his destination to find that a fire has destroyed the town, leaving “nothing but the rails and the burned-over country.” Everything is about the war, such as the wet shoes squelchy with water, paralleling Hemingway’s wounding in Italy, along a river, and the feel of warm blood filling his boots. Even the grasshoppers have all turned black from living in the burnt landscape, leaving Nick to wonder how long they would stay that way. It’s a beautiful piece of writing, and like much art concerning itself with the consequences of war, it is still germane today.

Not every writer will want to strip away all reference to the subject matter as Hemingway did, but understanding the concept of total immersion and how it will give you the confidence to write about a time and place alien to our modern experience is the key takeaway here.

I think of it as whispering details to the reader.

Marianne Moore defined the perfect poet: one who stocks their imaginary garden with real toads. If you immerse yourself deeply, you’ll be confident to write about your era with assurance, and a writer’s assurance is a better tool than any mountain of facts. But you need to amass the facts first in order to leave them behind.

Use Gardner’s 5 levels of psychic distance

Once you’ve amassed (and left behind) those facts, think about John Gardner’s notion of “psychic distance.” By that, he means the distance readers feel between themselves and the events in the story.

He applies it to all fiction, but it’s especially critical in historical fiction.

- Level 1 is distant and objective; grounds the reader in time and place.

- Level 2 begins to bring in personal information within the setting.

- Level 3 allows characters to emerge while the narrator is still in control.

- Level 4 goes deeper into a character’s thoughts and POV.

- Level 5 brings out the character’s voice fully; the narrator disappears.

Level 5 is where you find the meat on the bone.

A Level 1 narrator tells the reader that it’s a hot summer day in 1820 and Lucinda is worrying about the arrival of a new lord of the manor, who has a reputation for meanness. In historical settings it can be appealing to use Level 1 as a shortcut to dispense information, but it’s often dry and unrevealing.

Instead, in Level 5 Lucinda blinks in the hot sun as a bead of sweat creeps down her backbone. A horse and carriage kicks up dust as it draws to a halt, coating the assembled servants in a settling layer of grit.

That Level 5 description puts the reader in Lucinda’s shoes and tells us something about the new lord at the same time.

A scene can use all five levels, drawing closer to the physicality of events as it drills down from Level 1 to Level 5. This telescoping technique allows you to deliver whatever background material you think necessary, but the more your characters live at Level 5, the more rewarding to the reader.

Try these levels in your historical fiction. Hear the train whistle—what does it mean? Smell the horses—good news or bad? See the blue uniforms of the advancing troops—friend or foe?

Got questions on historical fiction? Let’s talk about them on Career Authors Facebook page.

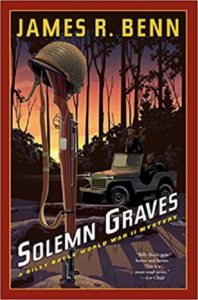

James R. Benn is the author of the Billy Boyle WWII mystery series. The 13th book, Solemn Graves, is being released September 4,

James R. Benn is the author of the Billy Boyle WWII mystery series. The 13th book, Solemn Graves, is being released September 4, 2018.

2018.