It’s one of the true joys of reading—the moment at the end of a book where you close the cover and think wow, what a terrific story.

Think, now, what do you really mean by that? Do you really mean: what a fantastic chase-scene ending in the capture of the bad guy? Do you really mean: oh, how perfect that the little boy sees his mother coming off the airplane? The moment the Wizard’s apprentice figures out how to do magic of her own?

Nope. Because those moments, those big climaxes and solutions and big bangs of revelation, memorable and pivotal as they are, aren’t the end of the story!

They’re only the beginning of the end of the story. In a satisfying novel, there will be the story’s “solution,” of course. But then the author must include how that solution affects the characters.

(If you haven’t read the posts on the Three Act Structure here on Career Authors, go back and do that.)

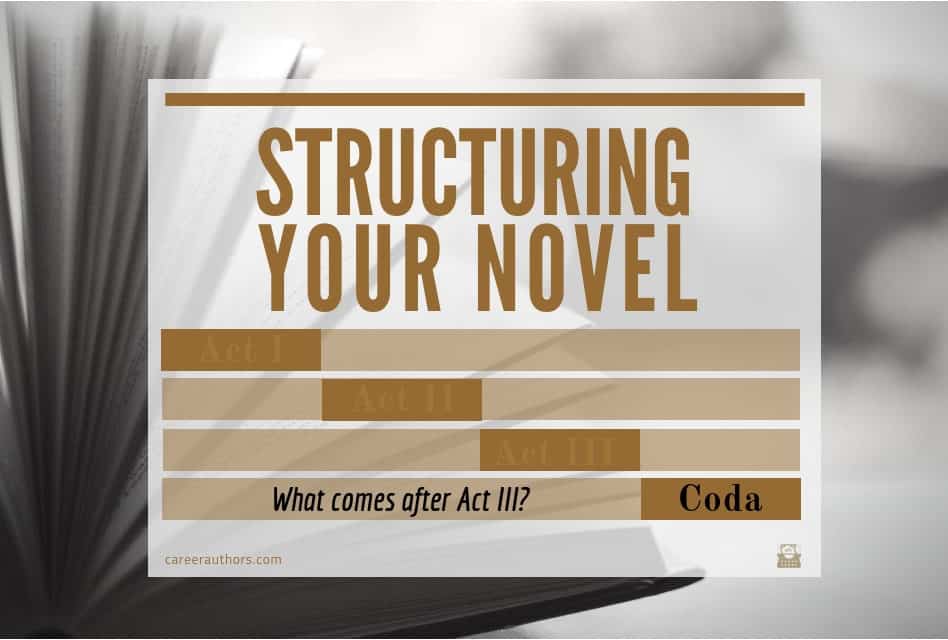

What we’re talking about today, the coda, is what happens after Act Three.

In music and dance, a coda is the concluding section, an addition to the basic structure of the dance. And it’s the same in a novel—a coda is an addition to the basic structure of the novel. The three-act structure is a basic necessity. But you must also have the novel’s final wrap-up.

The coda is the end of the ending

You might call it an epilogue, or call it “after,” or next year, or use a timestamp of some kind. Remember in the last Harry Potter, when Rowling fast-forwards to show us Harry’s future? The coda is the novel’s closing, the section that telegraphs to the reader: these characters are real, and their lives continue even after the book ends. It’s the time the author gets to say: here’s what this all means.

I was recently at a and event with Yrsa Sigurdardottir and Ragnar Johansson, the famed Icelandic thriller writers. And each of told us that their books ended twice. “Ended twice?” the interviewer asked. Yes, they said. There is the end of the plot, and then there is the end of the novel.

And I was the interviewer at an event with Harlan Coben, and he, too, talked about having multiple endings. One part of the story ends, then the next part, and then the next part, and then—the big final tying up of loose ends, and then maybe a final twist? And what it all means.

The coda is what leaves your readers satisfied, and with a feeling of finality, but also of continuation. Every loose end of your plot is wrapped up—and then there is the brief section that clarifies the result of that ending.

So what will be in your coda?

Ask yourself: what questions are left in my novel? Even after all of the plot elements are tied up in a nice tight ending, what might a reader wonder?

This is the place to return to your theme. The theme you have so beautifully set up in act one and continued throughout your novel. Is it revenge, redemption, depth of understanding or coming-of-age? What have your main characters learned, and just as important, how will they change and what will they do as a result? The coda allows your characters (and you) to make that clear.

It is not just catching the bad guy, for instance, it’s elaborating on what that means.

Emotionally, morally, judicially, and as groundwork for the future. Maybe it’s the understanding of the main character’s goal, or the declaration of a commitment, or an acceptance of a future journey.

A marriage is often used, because that moment of promise becomes a look into the future. If there’s a reunification—what does the reunification mean for the future? The eradication of a menace—but what does that new freedom mean for those who are involved?

More than plot

The coda lets reader see that you understand that your book is not simply about plot, but about understanding and depth and adherence to theme. This is where you can almost specifically state that theme. You’ll do it more gracefully than this, but something like: “Finally I understood how important family connections were, and I vowed I would never lose sight of that again. I felt like a new person, and more concerned with others than I was about myself.”

(Really, I understand that is terrible.) But you want to make it clear—in the voice and point of view of your characters—what has been understood or accomplished or realized or reached.

(And they all lived happily ever after is the simplest and shortest way to write a coda, but you would not do that unless you were writing a fairytale.)

It can the revelation of a huge twist.

It can be a fast forward, to show that the characters continue to live.

It could be a promise that a life will continue.

It might be a realization that everything that happened was a set up—did you see The Usual Suspects? More I cannot say. Be very careful with that, though. Anyone who watched the “it was all a dream” episode of Dallas will understand how dangerous that is.

How you want the reader to feel

The coda allows you, as the author, to choose the feeling that your reader will be left with as the book closes. Do you want them to feel happy, relieved, accepting, empathetic? Is this the moment that the reader bursts into happy tears, or reaches for the next in your series? That means you’ve mastered the coda.

Do you write codas in your novels? Let’s talk about that on the Career Authors Facebook Page. And then—get writing.