“But do not give it to a lawyer’s clerk to write, for they use a legal hand that Satan himself will not understand.” ~Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quixote

If you believe Cervantes, legal writing is incomprehensible and perhaps fraught with ill-intentions. Yet, successful authors with a legal background include such luminaries as Chaucer, Goethe, Balzac, Kafka, and Fielding, not to mention contemporary writers like Scott Turow, Nancy Allen, and John Grisham. Why do so many attorneys become successful storytellers? Because, in fact, the legal profession provides a fertile training ground for writers.

Conflict and Character

It’s a cliché but also a truism: good fiction requires conflict. The American legal system rests on the notion that conflict is essential to justice. Hence the term adversarial system. Even seemingly straightforward lawsuits often involve turmoil. Suppose a grocery shopper slips in the soup aisle and sues the market for negligence, claiming to have tripped on a fallen can of tomato soup. The market’s security video is choppy but seems to show an empty aisle. Another shopper walked in front of the camera just before the alleged accident happened.

“The market people tampered with the video,” the shopper claims.

“The plaintiff is a con artist,” the market responds.

This prosaic story, rife with conflict, also requires character analysis. Does the shopper have a history of making false claims? Does the market have a record of negligent cleanup? Does the grocery employee responsible for stocking the soup shelf hold a grudge against the shopper? And who is that mysterious person who just happened to obscure the camera’s view the very moment the slip-and-fall allegedly happened? The point is that attorneys train to address conflict and analyze character in circumstances that arise out of everyday life—which is exactly what successful fiction writers must do.

Wordsmithing

The rules of the U.S. District Court in Los Angeles provide that no legal brief may exceed 7,000 words—the length of a not-so-long short story. Briefs often address multiple complex issues. So, lawyers by court rule must follow Elmore Leonard’s advice: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”

These word-count strictures often improve writing. For example, the need to cut words discourages a writer from using the dreaded passive tense. The sentence Mary hit the ball requires fewer words than The ball was hit by Mary. Neither can overwrought adjectives and needless adverbs survive the final edit. The sentence In vociferously and disingenuously putting forth brazen and naked assertions blatantly devoid of any substance whatsoever, the defendant offends the well-established mandates of our system of justice mercifully becomes The Defendant’s legal arguments are wrong.

The takeaway: it’s not a bad idea for fiction writers to give themselves a word limitation, even though they might not stick to it. (Don’t worry about writing too few words, which is rarely a problem for the beginning writer.)

Deadlines

Early in my writing career, I attended a conference in which one of the instructors told a story of a friend who wrote beautifully but would always stop writing her novel eighty percent of the way in and instead begin something new. The ability to finish a book and finish it on time is a learned skill. For the attorney, failure to complete a project can result in a malpractice lawsuit and the loss of a client’s valuable rights. The law trains an attorney to finish the written work, an essential skill for anyone who wants to become a published author.

Collaboration/Revision

Attorneys-turned-authors tend to have less author’s pride in their work, and that’s a good thing. In law school, I wrote short piece for the law review. A “Comment Editor,” “Chief Comment Editor” and “Editor-in-chief,” respectively, all tore my article apart. Over my many years of practice, senior lawyers and clients have, sometimes brutally, made changes to my written product. Almost invariably, the product turns out better in the end.

Many fledgling writers resist editing, as if their written work is a precious artifact or even their offspring. But a written work—fiction, nonfiction, or legal—isn’t a precious object, but rather a form of communication that requires that the reader to understand and react emotionally to the speaker’s words. Excessive resistance to edits often results in poor communication and a novel that doesn’t sell. The takeaway: like an attorney serving a client, embrace the editing process and find effective collaborators.

Demystification

Although I aspired to write from an early age, I didn’t publish my first novel until relatively later in life. I believed becoming an author involved a mystical ability to transport any reader to a higher level of aesthetic consciousness. Not surprisingly, the necessity of becoming a “genius” intimidated me.

Author and personal editor Matthew Sharpe tells a story about going to a dental appointment and having his dentist ask, “What do you do when you don’t feel like writing?” Matt responded, “What do you do when you don’t feel like drilling teeth?” Once I decided to approach writing fiction the way I approached my job, writing fiction didn’t seem so daunting. I gave myself a deadline, wrote a not-so-wonderful draft, revised it, found editors whose suggestions improved the book, and finally got published. Novel writing became not a magical process but a wonderful, rewarding second occupation—all because I applied basic lessons I’d learned from my time in the legal profession.

Robert Rotstein’s legal drama, We, The Jury (Blackstone Publishing October 2018), is a USA Today best seller and a Suspense Magazine Best Thriller of 2018. With James Patterson, he is the author of The Family Lawyer, the title story of the New York Times best-selling collection. He’s written Corrupt Practices (2013, Booklist starred review); Reckless Disregard (2014, Kirkus and Booklist starred reviews), and The Bomb Maker’s Son (2015), a series

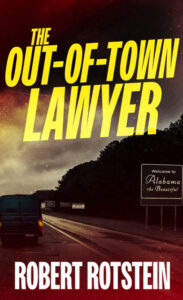

Robert Rotstein’s legal drama, We, The Jury (Blackstone Publishing October 2018), is a USA Today best seller and a Suspense Magazine Best Thriller of 2018. With James Patterson, he is the author of The Family Lawyer, the title story of the New York Times best-selling collection. He’s written Corrupt Practices (2013, Booklist starred review); Reckless Disregard (2014, Kirkus and Booklist starred reviews), and The Bomb Maker’s Son (2015), a series  about lawyer Parker Stern. Rotstein practices intellectual property law with the Los Angeles firm Mitchell, Silberberg & Knupp, LLP, and has represented all the major movie studios and record companies, as well as well-known directors and writers. His latest legal thriller, THE OUT OF TOWN LAWYER is available for sale now!

about lawyer Parker Stern. Rotstein practices intellectual property law with the Los Angeles firm Mitchell, Silberberg & Knupp, LLP, and has represented all the major movie studios and record companies, as well as well-known directors and writers. His latest legal thriller, THE OUT OF TOWN LAWYER is available for sale now!