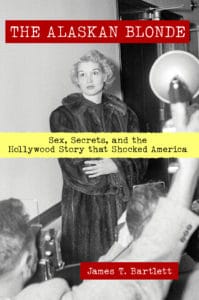

by James T. Bartlett

The murder of Cecil Wells happened in Fairbanks, Alaska, on October 17, 1953. At the time Alaska wasn’t a US territory – it didn’t become a state until 1959 – and soon after I decided to write a true crime book about this case, I found out that there was a real difference in record-keeping between the two entities.

That was just one of the challenges I faced while researching The Alaskan Blonde: Sex, Secrets, and the Hollywood Story that Shocked America; another was that fact that unlike many stories within the genre, I had no connection to this crime at all.

I wasn’t a victim’s family member or friend, nor a local journalist who had doggedly pursued the story. I was very much an outsider. An “Outsider” is what Alaskans call people from the Lower 48 states, but I wasn’t even that: I was born in England, nearly twenty years after the crime.

Surprisingly, this helped me during the research process. My accent broke the ice, but it was always followed up with the questions: Why are you interested in this? Why now?

When asking questions about sensitive subjects, you should have your own answers at the ready for those two questions, but for now, here are some top tips to start you off on researching your true crime novel.

1. Befriend librarians, archivists and history enthusiasts

The internet is definitely vital, blah, blah, but librarians, archivists, and history enthusiasts—the latter of whom are often volunteers—are utterly invaluable. They truly want to help, especially with intriguing problems. When I told them I was researching a murder, they seemed even keener.

If you take the time to explain what you’re doing, people will often go the extra mile to suggest ideas that neither you nor Google would ever come up with. Certainly librarians are the unsung and underfunded angels who will save your bacon, and make your project better.

Send a thank you card, and later give them a shout out in your book’s acknowledgements.

2. Track down and get interviews

All the principal players in my latest book were long dead. That meant I had to locate and contact their children and grandchildren, many of whom were at an advanced age.

Whether you reach out to potential interview subjects via email, social media, or even with a cold call, initially be brief but honest, and use a neutral tone. lf you’re a journalist of any stripe, say so: they’ll check you out before (or if) they reply. Reach out a few times too, as they might think it’s a scam, or that you’re a dirt-digging lawyer. Reassure them you are not!

3. Listen and don’t talk

In every interview be respectful and patient. Understand you may have to repeatedly explain yourself and your interest in this story before they grant you the privilege of talking about something that perhaps fractured their family for generations.

Try not to suggest ideas or imply theories, nor correct anything they say, even if your research has proved the opposite; they can read about it in the book later if they wish. Often people are in fact keen to talk, pleased someone might be able to shine a light on a historical black hole.

Occasionally you might find hidden treasure; they might share family photos, diaries, or other documents of significant relevance to your case.

Also, for several reasons it’s a good idea to have a smartphone app that can record phone calls and live interviews.

4. Get obsessed

Research can be the most enjoyable part of the writing process; it’s where you make the discoveries, and slowly develop and formulate how you’ll tell the story.

For true crime, this often means becoming utterly obsessed: buying every conceivably connected book, researching obscure papers and articles, idly Googling keywords, scouring eBay for items and generally getting lost down time-sucking online rabbit holes. Embrace it.

5. Visit where it happened

It was thrilling and unexpectedly emotional to visit Fairbanks and see the old courthouse, the building where the murder happened, the bridge where—perhaps—the murder weapon had been thrown from, and more. I went into a couple of bars too, and once the locals realized I wasn’t chasing the Aurora Borealis, memories, phone numbers and names started coming my way.

Visiting the town library is also a guaranteed jackpot. Locally-published books may be there and perhaps nowhere else. I walked into the Noel Wien Library in Fairbanks and asked the person at the reference desk about the Cecil Wells murder: perhaps she had heard of it? Turned out she was related to one of the people involved, and she had actually interviewed people about the case over a decade ago. Needless to say, that would never have happened if I hadn’t gone there.

Ultimately, you need to craft a story that’s as exciting and compelling to a stranger as it is to you, and that can be where kindly beta readers might gently explain that you’re not writing a Master’s Thesis.

And remember this: Every bit of research you leave out may still prove useful, possibly having a life in blog posts, articles, and especially live events. Think of this bonus material as surprises you have hidden up your sleeve!

Have you had edited material from your book research come in handy later? Share the what and how with us on Facebook.

Originally from England, James T. Bartlett’s latest true crime book, The Alaskan Blonde: Sex, Secrets, and the Hollywood Story that Shocked America, examines a sensational 1953 murder, sex and race scandal that began in then-territorial Fairbanks, ended with a suicide in Hollywood, and hit the pages of Life, Newsweek, Ebony, Jet, and other pulp detective magazines and newspapers across the Lower 48.

Originally from England, James T. Bartlett’s latest true crime book, The Alaskan Blonde: Sex, Secrets, and the Hollywood Story that Shocked America, examines a sensational 1953 murder, sex and race scandal that began in then-territorial Fairbanks, ended with a suicide in Hollywood, and hit the pages of Life, Newsweek, Ebony, Jet, and other pulp detective magazines and newspapers across the Lower 48.

He also wrote the Gourmet Ghosts alternative guides to crime, ghosts, and the history behind Los Angeles bars, restaurants and hotels, and as a travel/lifestyle and history journalist he writes for the LA Times, BBC, Westways, Hemispheres, High Life, Atlas Obscura, ALTA California, Real Crime, Crime Reads, Casebook.org, American Way and others.