By Patrice Gaines

I remember Vicki well, the student who illustrated what I had just said to workshop attendees about writing from a perspective of complete honesty.

“This means you have to heal any wounds that prevent you from being honest with yourself,” I warned. “Readers can spot a lie. And they won’t trust a narrator who is not totally honest.”

It means risking vulnerability. That takes courage. It may even mean going to a therapist before you attempt to write a very personal story. Or just admitting to blockages that may blind you from seeing clearly, or acknowledging that you aren’t sure you are absolutely right, or that events could have happened differently than you recall.

Being vulnerable on the page, before strangers, is not for the fainthearted. But you will be rewarded by loyal readers who will follow your every word because they trust you.

I was teaching “Writing Memoir,” but writing with emotional honesty is an important lesson whether you are writing non-fiction or fiction. Readers who know nothing about the technicalities of writing can smell a dishonest narrator.

I had known Vicki before my class, a thirtyish single mother with a heartbreaking story. But was she ready to write it? She wanted to try—and I wanted to guide her.

Everyone in the workshop received her five pages before it started. Vicki was going to give it voice by reading her pages aloud. Then she’d breathe deeply, the way we writers do to rid ourselves of the anxiety that comes before feedback.

At first, she read slowly. Her composition was about the night her husband stood in the living room in front of her and their five-year-old daughter, put a gun in his mouth—and pulled the trigger. Six other writers listened intently. Vicki’s voice was strong, then it grew louder. It was a story that by its sheer telling should have mesmerized us.

But something was askew. She was not a detached narrator, nor a woman still filled with disbelief. She was not a sorrowful widow, though her words begged for our sympathy.

Vicki was angry.

And this would have been totally acceptable if only she’d acknowledged this anger to herself. Instead, she’d written the piece as if she was only grieving, mourning a husband whom she loved. Her words belied the complexities of her true feelings.

When she finished, there was an uncomfortable silence. Vicki was breathless. Her audience was troubled. With some coaxing, her fellow writers admitted, tenderly, they were somewhat perplexed.

“I felt your anger more than anything,” an older woman finally said.

Vicki was surprised. “Anger?”

We all talked for another twenty minutes about how to make the scene say what Vicki wanted it to say. With this feedback, it became clear to Vicki: She wasn’t ready to write about her husband’s suicide. There were emotions she had bottled up and had yet to acknowledge

“If you’re angry, then say you are,” I advised. “It’s going to come out. Your anger is too real to be denied. It will, in fact, endear readers to you.”

Be honest. No words are big enough for you to hide behind. Readers will peep around them, see a fake, and walk away. Be fearless. Dare to be vulnerable.

Even the most accomplished wordsmith can be surprised by unexpected emotions when writing. Do you think writing is like therapy? Share your thoughts with us on Facebook.

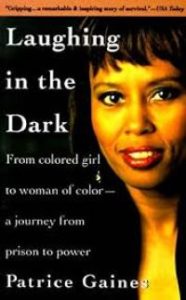

Patrice Gaines is the author of Laughing in the Dark and Moments of Grace. For many years, she was a reporter for the Washington Post, and she has won several prestigious awards for her journalism. Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including Essence and the New York Times Magazine. Her commentaries have been broadcast on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered” and NPR’s “Blues & Notes.”

Patrice Gaines is the author of Laughing in the Dark and Moments of Grace. For many years, she was a reporter for the Washington Post, and she has won several prestigious awards for her journalism. Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including Essence and the New York Times Magazine. Her commentaries have been broadcast on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered” and NPR’s “Blues & Notes.”

As a motivational speaker, Patrice travels the country, speaking at conferences, colleges, prisons and drug rehab programs, inspiring audiences with the incredible story of her life. More recently, she has focused on prison reform and assisting formerly incarcerated people. She co-founded a nonprofit, the Brown Angel Center, which gives a monthly workshop for women at the Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Jail. Patrice has received numerous awards for her humanitarian work.

Patrice is a contributor to How Black Lives Came to Matter in America, coming from Grand Central in Fall 2020. She lives in South Carolina and is at work on another memoir, Bending the Arc Towards Justice.

www.PatriceGaines.com

IG: therealpatricegaines

Twitter: @patrice gaines