I’ve been thinking about facts in the novel lately because I’ve been doing a fair amount of fact-finding for the book I’m working on that’s set in 1941. Of course, the historical novel requires a lot of research and we expect that the historical novelist spends weeks, months, years buried in archives and weighty historical tomes, pestering librarians, and diving down internet rabbit holes.

It’s daunting and I am suitably daunted, but two things have helped me hold my head above water. One is a wonderful remark I heard Sujata Massey, a historical novelist I greatly admire, make in an interview with Alison Gaylin at Murderous March. She mentioned that she’d ordered an expensive rare book, convinced it held the key to her work in progress, and then when it arrived, she found it too stultifyingly boring to wade through. The second is that I’ve always done research for my books and I’ve made a discovery.

As important as the research is, it’s just as important to know when to make it up.

So, I thought I’d talk a little about how I decide what should be real and what doesn’t have to be when I’m writing.

Being able to picture the setting is one of the things that makes a book real to me, and I struggle with books that never identify where they’re taking place. That’s not to say, though, that a novel’s city, village, or its grand manor house must exist on any known map. If it did, I might be tempted, like some readers I know, to point out the mistakes—the one-way streets drawn as two-way, the misplacement of the library, the erroneous naming of the founder. The danger for the writer, too, is if you set your book in a known place—Rhinebeck or Woodstock, New Paltz or Saugerties—and then write about its murderous mayor, you might find the mayor and their family knocking angrily at your door—or serving you with libel papers.

When you use a real place or event you have a responsibility to the people and events tied to it.

Some writers manage quite well with the real place (Alison Gaylin with Rhinebeck, Leah Konen with Woodstock, for instance), but in my novels, I prefer to create a fictional town with real neighbors. An imaginary garden with real toads, so to speak. The appeal of the Hudson Valley, where many of my books are set, is that I feel like I can slip a fictional place into its mysterious and misty folds. Woodstock may be just down the road, or perhaps Rhinebeck. We’re an hour or two north of the city and the river’s to the east or the west. In my book there might be an old mansion a little like the one down the road from me, but if I make its previous owner a murderer my neighbor won’t (I hope) be angry with me.

I think of the real landmarks surrounding my fictional places as anchors or tethers to the real world.

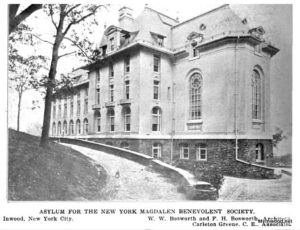

That’s been a good model for sorting the real from the unreal in plot and characters, too. My latest book The Stranger Behind You is set in Inwood, the northernmost neighborhood of Manhattan. It’s a real neighborhood—as both my daughters who live there will attest—rich in history. In doing research for the book, I discovered that there had been a Magdalen Refuge in what is now Inwood Park. I was fascinated to learn that there had been Magdalen Laundries—prison-like institutions for wayward women—in this country. It was just the kind of historical detail I love to use, and I thought it would add dimension to the modern #MeToo story I was telling.

I gleefully read articles in the New York Times archives about the beautiful architecture (like a French chateau!), the daring and sometimes fatal escapes, riots (much hair pulling and clothes rending), and mysterious poisonings. I also learned that the refuge became the Jewish Memorial Hospital in the 1930s and was torn down sometime later (I couldn’t find out exactly when). The fact that the building was gone gave me the freedom to resurrect it as a swank apartment building. Who wouldn’t want to live in a French chateau in Inwood Park overlooking the Hudson River, especially when it’s advertised as one of the safest buildings in the city and called The Refuge? Well, it could be that the chilling legends of its resident ghosts and mysterious haunting odor of laundry soap might deter some.…

I gleefully read articles in the New York Times archives about the beautiful architecture (like a French chateau!), the daring and sometimes fatal escapes, riots (much hair pulling and clothes rending), and mysterious poisonings. I also learned that the refuge became the Jewish Memorial Hospital in the 1930s and was torn down sometime later (I couldn’t find out exactly when). The fact that the building was gone gave me the freedom to resurrect it as a swank apartment building. Who wouldn’t want to live in a French chateau in Inwood Park overlooking the Hudson River, especially when it’s advertised as one of the safest buildings in the city and called The Refuge? Well, it could be that the chilling legends of its resident ghosts and mysterious haunting odor of laundry soap might deter some.…

Although I performed a little magic to put the Refuge back on the map, I hewed closely to the neighborhood geography otherwise. The church on the corner is really there, and the Irish bar my heroine goes to is a recreated version of The Indian Road Café, where our family has celebrated many birthdays. When I wrote scenes of my character Joan walking down the hill through the park, I was able to summon all my experiences of Inwood Park; when she goes to the Marble Hill train station, she’s on the real map of New York City.

Just as those physical landmarks are tethers to the real world, I used contemporary and historical events to anchor my fictional plot. The sexual predator that Joan exposes is fictional, but Joan references #MeToo cases that were all too real. I followed the Weinstein case, and read Ronan Farrow’s Catch and Kill, in order to have a sense of how a reporter investigates allegations of sexual harassment and assault. I also wanted a real-world sense of the power dynamics that perpetuate sexual harassment and assault in the workplace and protect its perpetrators. Although I wasn’t telling the stories of the real-life victims of sexual assault, I felt a responsibility to honor their stories by getting right the details of how these assaults happen, why they often aren’t reported, and what goes into uncovering them.

For the historical story that Joan’s nonagenarian neighbor, Lillian, tells her, I read numerous books on Murder Inc and organized crime in the 1940s. Lillian references real-life figures such as Abe Reles, the Murder Inc assassin-turned-informer; William O’Dwyer, the Brooklyn D.A. who turned Reles; and the “Kiss of Death Girl,” whose real name was Evelyn Mittelman. However, the Assistant D.A. who in my novel recruits Lillian to spy on a crime boss is fictional, as is the crime boss.

Real people are tethers for imaginary ones.

The mix of fact and fiction, the proportion of real to unreal, is a dance every writer must learn to navigate differently. There’s no steadfast recipe but, as Mary McCarthy says in her essay “The Fact in Fiction,” “The staple ingredient present in all novels in various mixtures and proportions but always in fairly heavy dosage is fact.”

What’s the ideal proportion of real to imaginary? Share your thoughts with us on Facebook.

Carol Goodman is the author of twenty novels, most recently The Stranger Behind You and The Sea of Lost Girls. Among her other outstanding novels are The Lake of Dead Languages and The Seduction of Water, which won the 2003 Hammett Prize, and, under the pseudonym Juliet Dark, The Demon Lover, which Booklist named a top ten science fiction/fantasy book for 2012. Her YA novel, Blythewood, was named a best young adult novel by the American Library Association. Her 2017 suspense thriller The Widow’s House won the Mary Higgins Clark Award. Her books have been translated into sixteen languages. She lives in the Hudson Valley with her family, and teaches writing and literature at The New School and SUNY New Paltz.

Carol Goodman is the author of twenty novels, most recently The Stranger Behind You and The Sea of Lost Girls. Among her other outstanding novels are The Lake of Dead Languages and The Seduction of Water, which won the 2003 Hammett Prize, and, under the pseudonym Juliet Dark, The Demon Lover, which Booklist named a top ten science fiction/fantasy book for 2012. Her YA novel, Blythewood, was named a best young adult novel by the American Library Association. Her 2017 suspense thriller The Widow’s House won the Mary Higgins Clark Award. Her books have been translated into sixteen languages. She lives in the Hudson Valley with her family, and teaches writing and literature at The New School and SUNY New Paltz.