If the reader doesn’t feel irresistibly compelled to turn the page at the end of chapter one, you are – how shall I put it – doomed.

Every Career Author has been a career reader for even longer, right? We’ve all had the experience of getting to the end of chapter one and saying…well, maybe. Maybe not.

And somewhere, the author would be wishing they’d tried a little harder. Or at least wondering what didn’t grab you.

How can you hit your first chapter ending out of the ballpark?

In an earlier post, I listed 17 great ways to end a chapter, from the emotional to the foreshadowing, from the terrifying to the philosophical, from portentous to promising. Plant a seed, make an assumption, draw a gun, make a wish. Set the stakes.

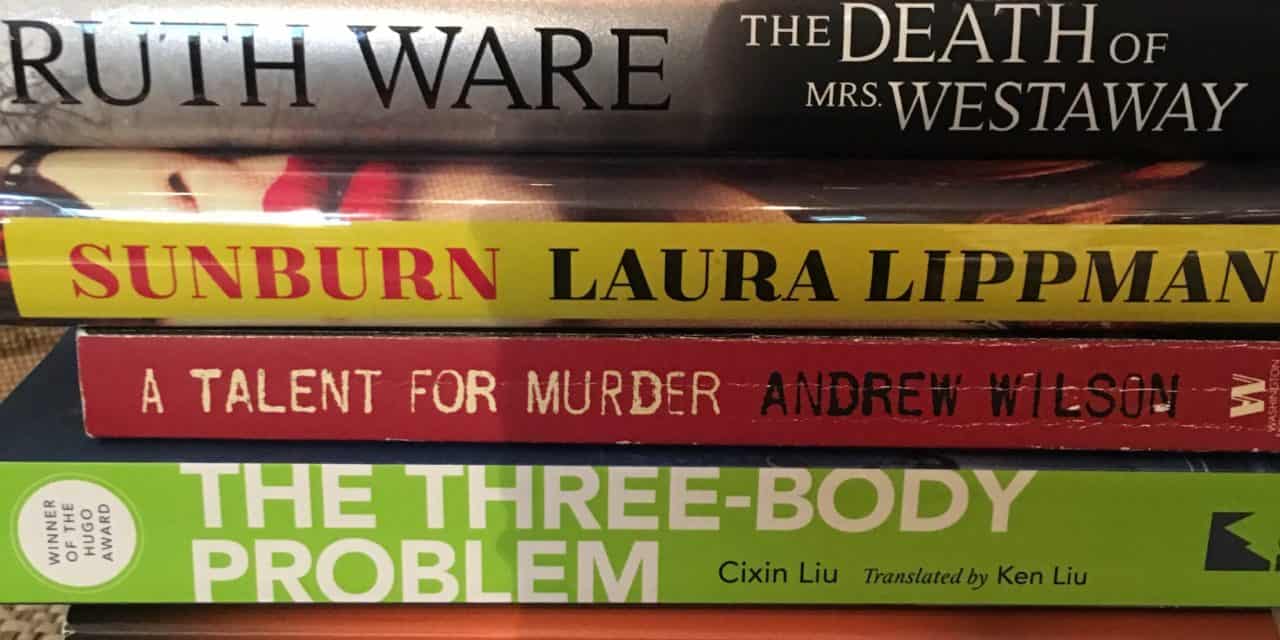

So I did an experiment. I picked a pile of books from my study (you do have piles of books, don’t you?) And opened each to the end of chapter one. I didn’t plan, I didn’t choose, I didn’t edit.

Let’s see what some authors – some you certainly know – have done to end their first chapters. Can they can point you in a helpful direction?

Hmm. That’s from 1943. Erle Stanley Gardner’s classic Perry Mason Solves the Case of the Buried Clock. Even though out of context it’s a wet-noodle last line, it really isn’t—the timing of what’s happening is important. And you see how the woman has attitude? And she’s foreshadowing that something’s going to be forgotten. So this last line makes you need to see if the characters accomplish what they’re supposed to. And whoa, poor Harley, right?

Okay, that’s the first chapter of my upcoming Trust Me. She’s just accepted an assignment to cover the murder trial of the notorious party girl Ashlyn Bryant—and, from what the reader knows is a reference to her husband and daughter, we know she’s got more on her mind than objective journalism, right? This reveals her determination, as well as foreshadows the revenge that’s on the way. What is “this”? What is she about to do?

See how much forward motion is here in The Gate Keeper by Charles Todd? Yes, it’s a long sentence, but doesn’t it make you feel what she does? The blood on her hands, and her frightened eyes, and her pallor show us she’s having some terrible realization. No dialogue! And see the alliteration? It doesn’t hit you over the head, but the Todds have thought about it.

In The Death of Mrs. Westaway, Ruth Ware goes for a realization, too. The main character, Hal, has just learned she’s been left a huge inheritance. But – uh-oh. Will you turn the page to find out what she does? Of course.

In Sunburn, Laura Lippmann offers a challenge. Don’t we wonder, too? What will happen if she does? Or if she doesn’t? Short. Scary. And we will turn the page to see.

This is – and we know it from the cover – the fictional explanation of where Agatha Christie went for those mysterious two weeks. In A Talent for Murder, Andrew Wilson gives the answer away right off the bat! Knowing he’s hooked the reader, Wilson offers a question we have to answer – does she do it?

In The Three Body Problem, Cixin Liu is beautifully subtle. Because it’s not only a clue, it’s a surprise. The reader knows from the page before that the person is dead—and the main character assumes she’s been murdered. But! Something is off-kilter. What’s really going on?

Well, yeah. What do you think is gonna happen? Will she be safe? In The Glass Room, Ann Cleeves uses our knowledge of how stories work to foreshadow some inevitable bad thing. But what? Turn the page.

Okay, this is tricky, but that makes it even more fabulous. This is V. M. Burns’ Read Herring Hunt. (Yes, Read.) The end of chapter one is part of the book-in-a-book motif Burns uses. The basic setting is contemporary, but the inside book is historical. And the end of chapter one is the end of chapter one of the inside book. So clever. And see? It still sets the stakes!

Classic! And in If I Die Tonight, Alison Gaylin knows it’s irresistible. Someone’s at the door! And because she’s a classy smart writer, she continues after the more cliffhanger-y “The doorbell rang.” She tells us who it is. And that makes it even more suspenseful. Now what’s gonna happen?

John Lescroart is so cool. In Poison, a character is told something important. But does he grasp it, or notice? Nope, he’s texting. So. It’s revealing, foreshadowing, timely, and wry. Uh-oh, we think. You should have listened.

What fun to unpack these! So take a look at how your first chapter ends. Does it stack up to the ones here that grab you? Can you make yours stronger?

Pick up the book beside you – what’s the last line of the first chapter, and what do you think about it? Come tell us on Career Authors’ Facebook page!