by Edwin Hill

“What do you do?”

“I’m a writer.”

It can be hard to say, and even harder to believe. I’ve tried the title on—writer—a handful of times, and then returned it, like a sweater that didn’t quite fit. I’ve asked myself what it meant to be something when that something didn’t pay the rent (or, for that matter, for a pack of gum).

Write the book you want to write

I remember the day I imagined calling myself a writer for the first time. It was 1979, I was eight going on nine, and I was sitting next to my older sister in the back of my parents’ yellow Ford Bronco on a white, vinyl bench seat. Every July, my parents took us on a month-long-family camping trip, and this year they’d decided to head from Massachusetts to the Dakotas. Something in the Bronco had broken—not unusual—and the heat wouldn’t turn off. It had to be 120 degrees outside. (If you knew my parents, you wouldn’t bother to ask if the Bronco had air conditioning, but since you probably don’t, the answer is not a chance.)

But none of this mattered. Nor did the views of the Badlands, or that we were heading toward Mount Rushmore, because earlier that day we’d hit a truck stop and bought a paperback copy of The Seven Dials Mystery, my first taste of Agatha Christie.

Agatha as muse

Reading those pages showed me the exact type of story I wanted to tell. I loved the language of that world, the elegance of the 1920s, the bridge games and the sherry and the intricate, seemingly impossible-to-solve puzzle that lay at the heart of the novel. When we returned home at the end of July and life got back to normal, like so many writers, I went to the public library and worked my way through every single one of Christie’s novels, marveling at the subterfuge of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, the ingenuousness of Murder on the Orient Express, and the brilliance in Curtain. My favorite of her novels to this day remains Crooked House, probably because its finale is among her darkest.

When I finished with the books in the library, I started calling myself a writer and tried to imitate Christie’s style. I still have some of those notebooks. In my stories, people call each other “Darling” while playing bridge and sipping sherry. Not much else happens. My handwriting back then is neater than it is today.

When I became a teenager, a lot of things were extremely important to me, but writing wasn’t one of them. I stopped calling myself a writer.

Envy as motivator

In the 90s, when I was in my twenties, a friend of mine called himself a writer, and I wondered what that even meant. No one—no one who mattered at least—had ever heard of him, but he boldly claimed the title as his anyway. He was a writer. And there was something untouchable and true in how he claimed it for himself.

He became famous—irrevocably, fantastically famous—the next year, in a way that was intoxicating, in a way that anyone who was near him couldn’t help but believe that a tiny piece of that fame could be taken and nurtured and made their own. I decided I wanted to be a writer. And I said I was a writer. I told anyone who asked.

I quit my real job. I moved. I got an MFA. I thought I found an agent, and for a moment it felt like maybe a piece of that fame actually was mine. Then my manuscript went nowhere and the agent moved on. You can’t live on the promise of being a writer, not in New York. So I found a real job. I moved. I got serious. I stopped calling myself a writer. And I stopped writing.

Timing is everything

In 2008, I read Kate Atkinson’s Case Histories and things clicked again. Reading this book—and the whole Jackson Brodie series—was like discovering Agatha Christie all over again, but a thousand times better. Here was an author doing what I would strive to do—a character-driven suspense novel, written with beautiful, purposeful prose, one that broke rules and didn’t stick to a tried and true structure—if only I was a writer. I finished Atkinson’s book and worked my way through the rest of the series. And then one night, I wrote an intro to a novel, a few pages, to see if I could still do it. It sat on my computer for about a year, and then I wrote another few pages, and tried a bit of outlining.

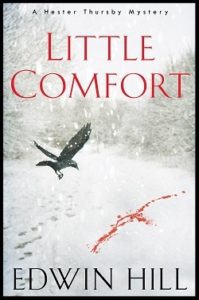

In the end, that intro didn’t make it into my first novel, Little Comfort, but a character from that intro, Sam Blaine, did. He’s named after my friend’s beagle, and he’s a charming psychopath.

Listen to criticism

I got an agent, but I didn’t quit my job or move. We shopped my manuscript around New York, and it went nowhere, but I knew enough now to see the process through to the end, to reshape the manuscript, to work with any criticism I was lucky enough to read. I trimmed here and expanded there, and my agent stuck with me through it all. I sold the book on November 9, 2016, and was the only person in my office with a smile on my face that day. (Check the calendar for what happened the day before.)

So, now it’s 2018, 39 years since that eight-year-old discovered Agatha Christie. Little Comfort will hit shelves on August 28, and I’m ready to try on that title one more time.

What do I do?

I’m a writer.

Was there a moment when you decided you could call yourself a writer? Share your story with us on Facebook.

Edwin Hill was born in Duxbury, Massachusetts, and spent most of his childhood obsessing over Enid Blyton’s “The Famous Five,” Agatha Christie novels, and somehow finding a way into C.S. Lewis’s wardrobe. After attending Wesleyan University, he headed west to San Francisco for the original dotcom boom. Later, he returned to Boston, earned an MFA from Emerson College, and switched gears to work in educational publishing, where he currently serves as the vice president and editorial director for Bedford/St. Martin’s, a division of Macmillan. He lives in Roslindale, Massachusetts with his partner Michael and his favorite reviewer, their lab Edith Ann, who likes his first drafts enough to eat them.

Edwin Hill was born in Duxbury, Massachusetts, and spent most of his childhood obsessing over Enid Blyton’s “The Famous Five,” Agatha Christie novels, and somehow finding a way into C.S. Lewis’s wardrobe. After attending Wesleyan University, he headed west to San Francisco for the original dotcom boom. Later, he returned to Boston, earned an MFA from Emerson College, and switched gears to work in educational publishing, where he currently serves as the vice president and editorial director for Bedford/St. Martin’s, a division of Macmillan. He lives in Roslindale, Massachusetts with his partner Michael and his favorite reviewer, their lab Edith Ann, who likes his first drafts enough to eat them.

Visit his website to learn more about his upcoming novel, Little Comfort.