I came to crime fiction from the world of literary fiction. I still love a good literary novel, but fully embracing the label of a suspense writer has made me somewhat impatient with the marketing distinctions that sometimes separate fiction into “literary” (well-written) and “genre” (not so well-written). Personally I’ve always subscribed to Henry James’s opinion, in “The Art of Fiction,” that “There are bad novels and good novels…that is the only distinction in which I see any meaning.”

Moreover, I’m realizing that my Master in Fine Arts program never taught me much about a key ingredient of every good story: suspense. Some writers may rely on it more than others, but even the most highbrow of literary types need to create a sense of tension and anticipation to keep the reader turning pages. I’m happy to have arrived in a genre where the value of suspense is freely acknowledged, and in my ongoing effort to get better at it, I’ve compiled a list of five ways to write a suspenseful scene.

Slow down

Sometimes when we think of slowing down the action in a scene, we think about lengthy passages of description, but that’s not what I’m talking about here. I’m talking about slowing down the action to linger on the details that the point of view character perceives as they walk into a room or engage in a conversation. Think about it: up to a certain point, anxiety (like desire) tends to make us more alert and more observant. If your character is approaching someone who might or might not have a weapon, she’ll be noting their body language and the way they carry themselves, on the lookout for any sudden movements. Including these details can make the scene more vivid and maximize tension by delaying gratification.

The ticking clock

A lot of people think of the ticking clock in terms of a story arc, as something that restricts narrative time to create a sense of urgency: the family has to decide whether to pay the kidnapper’s ransom before the deadline, or the hero has to defuse the bomb before it goes off. A few years ago, the writer Rebecca Makkai visited my fiction class and gave my students a tip that I still think about: incorporate the ticking clock not only into the story as a whole, but also into each individual scene. This is especially effective in suspense scenes (the protagonist needs to finish searching the house before the suspect comes home), but I think about it in terms of more everyday scenes too. Say two sisters are talking about their aging parents at lunch, but one is worried about her parking meter running out before the meal is over. The conversation will be more focused and more direct with that added pressure.

Pause

Sometimes the snake on the path is just a stick. If your point of view character is tuned to a pitch where they see danger everywhere, they may sometimes see danger where it doesn’t exist. At moments like these, the protagonist may laugh and let their guard down, which allows the reader to relax as well. This might provide a welcome break from the tension, and it will also allow you to surprise the reader when the real threat comes along.

Put the reader in your character’s body

We all know that internal sensations say a lot about the character’s state of mind, but sometimes it’s hard to express those feelings without resorting to cliché. I struggled for years trying to find a new way to say “She was scared” or “She was on edge” until I found Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi’s invaluable guide, The Emotion Thesaurus. Ackerman and Puglisi chart just about every imaginable human emotion and suggest ways to express them through both physical signals and internal sensations. At one point in my life, I might have thought of this as cheating, but I don’t think that way anymore.

Writing is hard; help is good.

Get to the point

A suspense scene is only as good as its payoff. You can have as many ticking clocks as you want, but if the scene just peters out when the timer goes off, the tension will fizzle. Ask yourself where you want your reader to be at the end of the scene: what have they learned, or failed to learn? What possibilities have been opened up or foreclosed? Does the protagonist understand their situation better than they did when they walked in, or do they have even more questions?

I don’t mind admitting that I wrote this list partly to remind myself of the things I should be thinking about every day when I sit down at my desk. Suspense doesn’t come easily to me, and for that reason, I need to be more intentional about it than I do about other aspects of writing. Luckily, like many other aspects of fiction, it’s a learned skill.

How are you all intentional about writing suspense? Let’s talk about it on the Career Authors Facebook page.

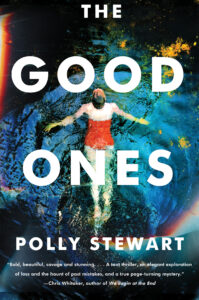

Polly Stewart was born and raised in the Blue Ridge, where she still lives. Her short fiction has appeared in Best New American Voices and Best American Mystery Stories, and in Epoch

, Alaska Quarterly Review, as well as other journals. She writes a new monthly interview column for Crime Reads called The Backlist, and her nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times and Poets & Writers, among other publications.

, Alaska Quarterly Review, as well as other journals. She writes a new monthly interview column for Crime Reads called The Backlist, and her nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times and Poets & Writers, among other publications.

THE GOOD ONES is Polly Stewart’s debut thriller. https://www.pollystewart.com/