By Debra Ginsberg

Many years ago, I ran into an acquaintance I’d known in my restaurant days, before I’d published my first book. We were standing at a stoplight, waiting to cross the street, and she asked me if I was working on a new book. I told her that my third memoir was about to be published.

“Huh,” she said. “Another memoir? I guess we’re going to know every single thing about you, aren’t we?”

“Well, no,” I said, “you don’t know everything about me. You only know what I’m choosing to tell you.”

To my relief, the light changed then and her dog dragged her across the street and away from me so that I didn’t have to further justify my apparent need to overshare my life for publication. But as I continued to chew over her comment, I realized that what I’d said wasn’t really a justification for memoir, but the definition of it.

A memoir is different from an autobiography in that autobiography takes into account all the facts, names, events, and dates of a life—the entire life, with all of its details. A memoir, on the other hand, is one piece of that life.

LESSON #1: Even though a memoir can encompass many years, it zeroes in on one theme, one event, one relationship, or one period in a life.

A memoir is targeted, but hazier and much more impressionistic in its approach. In any life, there are countless stories; a memoir tells one of them. This is how I, and many other writers, have been able to write multiple memoirs. I’ve always thought of myself as a series character and my life as the series.

We write memoir because we want to share our stories with others. And part of why we want to share our stories with others is because, while our individual experiences are unique to us, our experiences in general are common to all humans.

LESSON #2: Memoir sits at the intersection of the personal and the universal.

By sharing our experiences in this way, we connect with readers and they with us. For writer and reader, it is both an intensely private and public experience.

Most of the memoirists with whom I’ve worked know that they want to share their experiences in this way—they know the why of it. Most, too, know generally which aspect of their lives they want to write about. Far fewer, however, know the how of memoir. Our lives are big and sprawling and packed with individual tales. How do we choose which one we want to tell and then, how do we tell it?

LESSON #3: The first step is to narrow the focus.

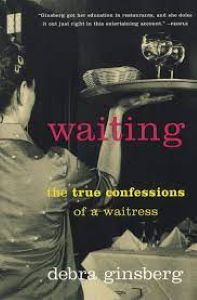

Will your memoir be about your unhappy childhood (as Frank McCourt wrote in Angela’s Ashes, “the happy childhood is hardly worth your while”)? Will it be an inspirational travel memoir (Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love)? A food memoir (Taste by Stanley Tucci)? A memoir of loss and grief (The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion)? A “profession confession” (my own Waiting: The True Confessions of a Waitress)? A memoir of your relationship with your mother (You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me by Sherman Alexie)? Coming of age (The Liar’s Club by Mary Karr)? Or a hybrid (Michelle Zauner’s beautiful story of food, grief, and her Korean mother, Crying in H Mart)? When we think about writing our memoirs, clusters of scenes and memories play in our minds over and over again. Identify those and examine them carefully. This is what you want to focus on.

The next step, and arguably the much more difficult one, is to figure out how to take that theme, event, person, place, or time period and structure it as its own story. While a story has a clearly defined beginning, middle, and end, our lives are ongoing. We have a beginning, middle, and a now. But we’re isolating a discrete part of our life in a memoir.

LESSON #4: Even though our lives continue (and maybe even shape our memories of the time we’re writing about), the story we’re writing has to have a specific stopping place.

That stopping place may actually be right now or it may be last week, a month ago, five years ago and so on.

When I wrote Raising Blaze: A Mother and Son’s Long, Strange Journey into Autism, a memoir about my son, I was recounting events up to the moment I submitted the manuscript to my editor. At the end of that book, I had just decided to take my son out of the disaster of public school and homeschool him. It was a cliffhanger—for me and the book—but I’d gone as far as I could go in real time.

Waiting was much easier to structure; I’d spent twenty years waiting on tables and those experiences became the story. Plenty of other things happened over the course of those twenty years, but if they weren’t part of the waiting theme, they weren’t included.

My third memoir, About My Sisters, was by far the most difficult to structure. Here, I was writing about my three sisters and my relationships with each of them individually and about all of us together. It seemed an impossible task to corral all of that into a structured story. For almost a year, I just wrote down individual scenes and thoughts—anything to keep moving—while I tried to hammer out a structure. Finally, I settled on the structure of a single year. There is either a holiday, celebration, or birthday for every month of the year in our family, so I led each chapter with that event and used it as a springboard into a connecting scene from the past with one or more of my sisters.

In each memoir, I began with a scene that reflected the essence of the memoir (waiting on a particular table, a conversation with my son in the supermarket, the death of my mother’s only sister) and then used that as a way into the story.

Discovering your ending—or where you’ve landed in the journey may not become totally clear to you until you’re well into your memoir, or maybe even at the end, but it will help you immeasurably to have an idea of where you want to end up.

LESSON #5: Once you do know that ending, make sure that the rest of the memoir reflects or leads us towards it.

Your ending should feel natural, as if this was the point all along, not something you decided at the last minute.

LESSON #6: A memoir does not have to focus on a harrowing, extreme, or traumatic event in order to be successful or compelling.

An exciting story about a trip to the grocery store can be a more involving read than a boring one about being rescued from a sinking ship. Every one of us contains a legion of stories. Which one will you choose to tell?

What do you think is the most challenging aspect of writing a memoir? Share your thoughts with us on Facebook.

Debra is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling memoirs, Waiting: The True Confessions of a Waitress, Raising Blaze: A Mother and Son’s Long, Strange Journey Into Autism, and About My Sisters and the novels Blind Submission, New York Times Notable and SCIBA Mystery Award winning The Grift, Indie Next and Barnes & Noble Pick The Neighbors Are Watching and SCIBA Mystery Award winner, What the Heart Remembers. Debra’s work has been translated into fourteen languages. Her son, Blaze Ginsberg, is the author of his own memoir, Episodes: Scenes from Life, Love, and Autism. She lives in Southern California.

Debra is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling memoirs, Waiting: The True Confessions of a Waitress, Raising Blaze: A Mother and Son’s Long, Strange Journey Into Autism, and About My Sisters and the novels Blind Submission, New York Times Notable and SCIBA Mystery Award winning The Grift, Indie Next and Barnes & Noble Pick The Neighbors Are Watching and SCIBA Mystery Award winner, What the Heart Remembers. Debra’s work has been translated into fourteen languages. Her son, Blaze Ginsberg, is the author of his own memoir, Episodes: Scenes from Life, Love, and Autism. She lives in Southern California.

A publishing industry professional since 1992, Debra Ginsberg has been editing books of all genres for over twenty years. She has reviewed books for The San Diego Union-Tribune, The Washington Post Book World, and Shelf Awareness, conducted writing workshops in four Western states, and contributed to NPR’s “All Things Considered.”