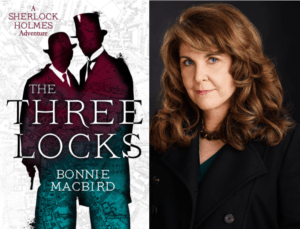

My fourth Sherlock Holmes novel, The Three Locks, was just released in the UK and the US. While I may appear confident in interviews, fears and self-doubts dog me, as they do most writers. However, I have developed a reliable writing process that has allowed me to remain productive through deadlines, deaths in the family, travel, severe illness—and now over a year of total lockdown during the pandemic. It’s a solid process, yet I would not have arrived at it without having designed and taught a writing class at UCLA Extension Writer’s Program.

To ensure universal improvement among students at vastly different skill levels, I wanted a kind of jujitsu technique to remove anything that might stand in their way of writing and focusing attention on attainable goals. Everyone has heard the adage “Teach to learn.” But teaching writing lit a fire under my own writing process in ways I never expected.

Welcome, I see you, now write

On Day One of class, I congratulated every student for the nerve it took to walk in the door. Writing and publicly sharing takes bravery. As one who has been an actor and a writer, I can say that writing is the far more revealing art. Onstage, you are costumed, clothed in a role, telling a story that has been scripted for you. But as a writer, you stand naked on the page. Everything that is there is you, unadorned and vulnerable.

How do you get better at something?

The obvious answer is practice.

If you’re a musician, it’s the only route to Carnegie Hall. This is true for the beginner, but also for the musician at the top of her game. A famous violinist once gave a performance at our home, and after the audience left and she was alone in the music room, what did she do? Champagne to celebrate?

No. She practiced for three hours. For the next concert.

We all can improve with practice, but how do you practice writing? Most writers only want to work on the important stuff: the screenplay that will sell or the Great American novel. My students were allowed the luxury of playing scales before the concert. Of course, later, play the piece, too. But, first, do the scales.

If this seems familiar, please read on. Julie Cameron’s Morning Pages and Natalie Goldberg’s zen writing practices are similar. Both are excellent at silencing the critic. Tim Gallwey’s techniques and Betty Edwards detailed steps toward drawing similarly help focus attention. These gifted teachers informed and inspired the Write-Outs.

Write-Outs do three things: They hush the inner critic, they develop the instinct for quality, and they embed the notion of structure.

That’s a lot of bang for the buck.

The Write-Out “Go!” instructions

- Get a new notebook just for these exercises. Students were asked to bring one to the first class. I had some on hand for those who forgot. Not a fancy thing. Not precious. Just a simple lined notebook.

- Handwriting only, because this is a profoundly different brain connection. Write quickly. One important rule: Keep the hand moving. Don’t stop writing.

- Write to a timer. 5 minutes at first, then 10 minutes after your first week.

- What you write is inspired by a single WORD … which is revealed just before starting the exercise. Write whatever comes to mind after hearing that word, and if you can’t think of what to write, write about being stuck. But keep your hand moving. Return to the word. Like the meditator returns to the breath, like the parent takes the child by the hand and brings him back to the path. No recrimination, just a gentle redirect. Back to writing about this.

- Write at Speed. Don’t stop and think. If you keep the hand moving, fill the page, you have won.

“Go!”

I’d give my students one word to set them off.

Blue.

Halloween.

Breakfast.

Fear.

These “evocative words. are designed to trigger memories, emotions, anecdotes, metaphors. In my class, triggering was not a fearsome word; it was a diving board into one’s imagination.

I asked my student writers to let go and engage. In this safe space, free themselves to react in words. Words just for them; no one else. If they poured out their guts, terrific. They didn’t need to share. If they heard the suggested word and wrote a poem, a memory, a free association, the beginning of a story… all good. Dance with the word, dig behind the word, uncover its hidden meaning. Reveal its meaning to you. Try on different meanings.

Here’s the word … And you’re off!

Say it aloud?

After they finished writing, I asked for volunteers to read from their Write-Out. I reminded them there was no pressure, only if they really wanted to.

I always got a volunteer. However, before they read, I would introduce another concept.

Directed Listening

Here are the rules for listeners:

- Listen silently. As the writer reads their prose, say nothing, but take note of anything that particularly sticks out for you. Jot it down.

- Pay careful attention. Laughs are okay. No groans. No tsks. No sounds allowed except laughter.

- Remain quiet. Afterwards, voice NO opinion, not even a positive one.

- Echo back. Without any comment, repeat verbatim any words, phrases or sentences that “struck you.” Say the words as you heard them.

For example, perhaps these careful listeners noted “the man with red ears,” “tasted like cold iron,” “couldn’t ever never forever,” “her thin-lipped grin,” or “barking and barking and barking.”

The result of directed listening in the classroom is threefold. The writer feels “heard,” and also safe. Most importantly, the writer learns what parts of their writing “landed”—or had an impact on their audience.

This exercise was tremendously empowering for my students. Three weeks in, almost all of them were clamoring to read aloud.

Building on the Write-out

My students were also assigned to do this exercise every day at home and report in. I posted the “Word of the Day” online at 12:01 a.m. They were instructed not to pull it down until ready to write. No premeditation…

Some found it easy. Many found it challenging but stuck with it. Others complained of hand cramping (yes, at 5 minutes!), for which they were instructed to do a simple stretch.

Some writers were working out trauma, some ballparking story ideas, and our classroom was a place to feel safe. No need to share, just to process.

The next level

Once my class was on track and diligently doing their Write-Outs, in the weeks that followed I extended the directed-writing sessions to ten minutes. And I added another layer of instruction.

Bring it on home

I kept a stopwatch and would announce, “Halfway there,” “One minute to go,” or “Thirty seconds to go.” At one minute left to go, they’d hear a coaching line: “Begin to bring this on home.” With thirty seconds left, “Bring this home now!”

My students knew this meant it was time to wrap up the ending, to make their point. Ask a leading question. End the story. Close the description. Stick the landing like a gymnast. Boom!

After I started issuing this instruction, the quality level ratcheted up. Now my students were writing to two externals – artists might call these “freeing constraints” – the specific word they’d been given and the need to stick the landing.

Unless we are journaling, all professional writing is writing to externals.

We need both freedom and structure at once.

We also need to press through— despite distractions. Career authors need to get good at doing this.

This creative mental state is what’s needed when drafting a scene of a screenplay or the chapter of a book. A writer may have either a vague or specific idea of what they’re doing, the setting or the action … but to get the scene written they must have freedom of thought and close down the critic (no-time-for-this-keep-the-hand-moving).

This is the secret sauce. It’s a practice that pays off. And these same techniques I use today as a pro.

When a storm is raging inside my head, a tug of despair, a miasma of jitters, a seductive invitation to play or waste time, a shattering distraction of noise or chaos or bodily discomfort, a stone cold fear, a yawning emptiness devoid of ideas … all this can hit me as I sit at my desk. I turn my next chapter into a Write-Out.

This chapter. This idea. Just for today. Pick a word. A sentence. Write a first draft. No one is looking. Keep the hand moving. Bring it on home.

Try it

Use this exercise with your writing group. While randomly doing write-outs on completely unrelated topics, a fair number of my students reported insights into a Work in Progress or an idea for a new project. Surprising how it works….

How do you break through writers block? Share your writing secrets with the rest of us on Facebook.

The author of the Sherlock Holmes adventures, The Three Locks, The Devil’s Due, Art in the Blood, and Unquiet Spirits, Bonnie MacBird is a produced screenwriter and playwright, as well as an accomplished stage actor and writing teacher. She holds degrees from Stanford in music and film, and when she’s not writing Sherlock Holmes adventures, she moonlights as a theatre director and audiobook reader. She divides her time between Los Angeles and London. Visit Bonnie at www.macbird.com

The author of the Sherlock Holmes adventures, The Three Locks, The Devil’s Due, Art in the Blood, and Unquiet Spirits, Bonnie MacBird is a produced screenwriter and playwright, as well as an accomplished stage actor and writing teacher. She holds degrees from Stanford in music and film, and when she’s not writing Sherlock Holmes adventures, she moonlights as a theatre director and audiobook reader. She divides her time between Los Angeles and London. Visit Bonnie at www.macbird.com