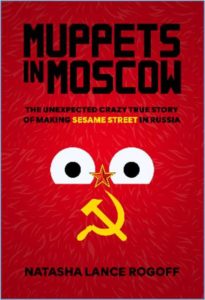

By Natasha Lance Rogoff

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the timing appeared perfect to bring the TV show Sesame Street to millions of children living in the former Soviet empire. With the Muppets envisioned as ideal ambassadors of Western idealistic values, I, like many Americans was swept up in the euphoria of imagining the new Russia as part of the Free World.

But as the American executive producer of Ulitsa Sezam (Sesame Street in Russian), I found myself thrown into the surreal landscape of Moscow television where bombings, murders, and political unrest were near-daily events. During our production, several heads of Russian television—our close collaborators and prospective broadcast partners—were assassinated. One was nearly killed in a car bombing—a car I was in just three weeks earlier after negotiating our deal. Also, our production office was taken over by soldiers with AK-47s.

Many American friends told me I should get out of Moscow while I still could. But what made me stay, even in the face of the physical violence jeopardizing the production, were the fascinating cultural battles that touched almost every aspect of the show—from the scriptwriting to the music, to the creation of the Slavic Muppets themselves. I discovered that adapting the American children’s show in Moscow often pitted the progressive values of Sesame Street against three hundred years of Russian thought.

The clash of divergent views about individualism, capitalism, race, education, and equality offered a window into the cultural discord and conflict between East and West. This would make for a great book, I thought.

That was almost thirty years ago. I started writing Muppets in Moscow in 1996, immediately after our television show first aired across the former Soviet empire’s eleven time zones. At the time, I understood our experience was unprecedented and our success remarkable considering the obstacles we faced. Sesame Workshop, the non-profit company that produces Sesame Street, had exceeded their greatest expectations. Ulitsa Sezam became a hit, broadcasting to tens of millions of children throughout Russia, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, and many other new independent states. The TV series continued airing well into Putin’s era.

I worked on the memoir off and on for several years and then, life interfered. I gave birth to two children, one with serious medical issues. I also had a full-time job, and eventually I put down the manuscript.

Into a downstairs closet went ten boxes of documents: transcribed audio and videotaped interviews that had been recorded during production, photographs and copious notes from the 1990s, and journals that I had kept throughout the production, detailing events and conversations as they’d happened. For years, my husband begged me to throw these boxes away.

My attention returned to Russia in 2017 after Trump was elected and the Russian government was accused of interfering in the U.S. electoral process. I traveled back to Moscow and filmed a video, “Russian Millennials Speak Openly about America.” This short film chronicled the views of young Russians. I hoped it would demonstrate to Americans (and to Trump) that Putin was not America’s ally. I had thought about calling the film, “Hey Trump: Putin is not your Bro!” When I posted the video on YouTube, it went viral, helped along by thousands of Russian cyber trolls criticizing the film and me. And then, the pandemic hit—making me a hostage in my home, along with everyone else.

During the immobility of Covid, and as Trump continued his praise for Putin, the contents of those cardboard boxes beckoned—treasure awaiting me in the downstairs closet.

The experience of my Moscow and American colleagues creating Sesame Street in Russia offered hidden jewels—numerous lessons about the culture clash between East and West—which suddenly seemed more relevant than ever.

Recalling my own frequent befuddlement over the Russian character, I thought my own story about Muppets, murder, and Moscow might possibly contribute to a greater mutual understanding. After all, this experience—which some might describe as an ordeal—only increased my love for the Russian people. I dug out those boxes from the closet and restarted work on the book, using the manuscript I had from years earlier and all the documents I had moved with me from one apartment to another, and eventually to our house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. So many years later, these materials, in addition to correspondence with my family, enabled me to reconstruct events.

Structuring the book was difficult because the historical narrative was so complicated and also unfamiliar to most Americans. I used a whiteboard to organize the book’s chronology, marking the car bombing, the first assassination, the second assassination, the office takeover with AK47s. But the whiteboard was too small. I created an Excel spreadsheet with columns and dates indicating historical events, key plot points and important emotional transitions. Once this four-hundred-page document was finished, I wrote an outline.

Then, I spent six months trying to teach myself how to write a memoir. Thank God for the internet, Masterclass and Reedsy blogs. I also read other writers’ memoirs: Bird by Bird, The Liar’s Club, The Year of Magical Thinking, Gertrude Queen of the Desert and many others. I also returned to great novelists I had read in my youth: Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Nabokov, reading their books aloud, trying to understand how these brilliant authors had found their voices.

Throughout, I thought my goal was hopeless, impossible, too much work, but for some reason I persevered.

The writing of the book was brutal. I rewrote chapters hundreds of times. My ass hurt. My back hurt. And then, after six months of writing, I discovered that some of the dates in my grid were wrong. I had to completely restructure the damn book!

After I had already interviewed fifty former Russian and American colleagues on Facetime and WhatsApp, my publisher informed me that anyone quoted would have to sign an agreement for their words to appear in my book. I wanted to cry. Here I must mention how very grateful I am for the encouraging support of my husband and grown children (who had moved back home during Covid). Sometimes it was only my daughter’s chocolate chip cookies that kept me going.

Despite occurring years ago, the incredible, eye-opening, and ultimately rewarding experiences of me and my brave Russian colleagues offer valuable lessons in international cooperation. The underdog success of Ulitsa Sezam inspired me to keep going and finish Muppets in Moscow.

A Russian friend told me that the reason it took me thirty years to write the book is that I had to first get over the delayed trauma of making a TV children’s show juxtaposing Sesame Street’s lighthearted comedy against a backdrop of bombings, assassinations, as well as a creative team that had at first insisted Russian children would hate the Muppet-style puppets made of soft foam, as opposed to traditional Slavic hardwood puppets. However, today’s world, one just as rife with conflict and misunderstanding, seemed the right time to share this tumultuous story of creativity in the face of repression. Like the Muppets, my goal is to make people smile, laugh through their tears, and think about how art is capable of building bridges.

Is it time for you to write your memoir? What’s holding you back? Share with us on Facebook.

Natasha Lance Rogoff is an award-winning American television producer, filmmaker, and journalist who has produced TV news and documentaries in Russia, Ukraine, and the former Soviet Union for CBS, NBC, ABC, and PBS. Lance Rogoff executive produced Ulitsa Sezam, the Russian adaptation of Sesame Street, between 1993 and 1997. She also produced Plaza Sésamo in Mexico. In addition to her television work, Lance Rogoff has reported on Soviet underground culture as a documentary director and magazine and newspaper writer for major international media outlets. Today, Lance Rogoff produces content for television and digital platforms and is the CEO and founder of an ed-tech company. An associate fellow in Harvard University’s Art, Film, and Visual Studies department, she divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts and New York City.

Natasha Lance Rogoff is an award-winning American television producer, filmmaker, and journalist who has produced TV news and documentaries in Russia, Ukraine, and the former Soviet Union for CBS, NBC, ABC, and PBS. Lance Rogoff executive produced Ulitsa Sezam, the Russian adaptation of Sesame Street, between 1993 and 1997. She also produced Plaza Sésamo in Mexico. In addition to her television work, Lance Rogoff has reported on Soviet underground culture as a documentary director and magazine and newspaper writer for major international media outlets. Today, Lance Rogoff produces content for television and digital platforms and is the CEO and founder of an ed-tech company. An associate fellow in Harvard University’s Art, Film, and Visual Studies department, she divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts and New York City.

Publishers Weekly called Muppets in Moscow “a thrilling debut” and the Wall Street Journal declared it “sparkling.” The Daily Beast said it was “fascinating and sometimes horrifying” while the Philadelphia Inquirer deemed it “hilarious and eye-opening.”

Is it time for you to write your memoir? What’s holding you back? Share with us on Facebook.

Website: www.natashalancerogoff.com

Facebook: Natasha Lance Rogoff | Muppets In Moscow

Instagram: @Natasha.Lance.Rogoff

Twitter: @LanceRogoff