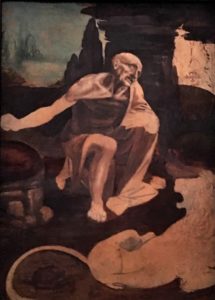

Currently on loan and displayed at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is an unfinished Leonardo da Vinci painting, St Jerome Praying in the Wilderness. This painting is of especial interest to artistic scholars because is it unfinished. Da Vinci’s techniques can be observed here like nowhere else.

St. Jerome wears a toga-like garment, but the complete article of clothing has not yet been painted. Instead, we see a man’s torso. Da Vinci’s intention was for the torso to disappear in the finished painting; it would be draped over by more white fabric. The painter planned to cover up his work. Infrared reflectography has shown even more of da Vinci’s underdrawing.

St. Jerome wears a toga-like garment, but the complete article of clothing has not yet been painted. Instead, we see a man’s torso. Da Vinci’s intention was for the torso to disappear in the finished painting; it would be draped over by more white fabric. The painter planned to cover up his work. Infrared reflectography has shown even more of da Vinci’s underdrawing.

This layering strategy is instructive for novelists. Writing fiction involves creating a background for fully realized characters. Successful novelists present their readers with an understandable context for their book’s events.

But readers need not see all the moving parts. (Don’t get caught like the wizard behind the curtain in the film version of The Wizard of Oz.) Remain unseen while operating the controls. This is true even when writing a novel in the first person point of view. A fictional character may be a story’s narrator, but the author creates the world and manipulates events.

The people in your head

Each character has a back story. Just as you have grown and developed, they too have evolved—in your fictional world—to become the realistic characters they are when the story takes place. While every aspect of their make-up is not on the page, readers understand that each person in a story is unique with their own past.

While an unfortunate seventh grade gym experience climbing a rope may inform an author’s understanding of a character called Eddie, it’s unlikely that every reader needs to know that much. Still, based on the author’s other characterizations, (if they thought about it) readers might guess that this dude Eddie flunked gym class. The author knows more than the reader: this qualifies them to tell the story.

What you need to know is not necessarily what your reader needs to know.

Crafting a dynamic, believable scene involves understanding its characters. Fully knowing them adds authenticity to the story. But, as always, good storytelling involves editing. Da Vinci edited out St. Jerome’s torso, though he could still picture it in his head.

Location, location, location

In Da Vinci’s paintings, we can imagine the landscape continuing outside the picture frame. He paints a slice of life. Fiction readers also document moments in time, and readers should be able to picture a scene’s setting in their head—even if its description is transmitted with brevity or utility.

Short (but concise) setting descriptions can provide purchase for a reader’s imagination, so their creative vision can take off on its own.

But, still, never fail to ground the reader: setting should be clear. Is that free-floating dialogue among characters occurring in a church or a bathhouse? Context is relevant.

Or it may be that a story’s setting is highly germane to its meaning and is described in luxuriant detail. Maybe it matters very much to the character Greta that outside her bedroom window cardinals are singing in the flowering tree.

Either way, you can’t skip setting. Readers of commercial fiction should never get lost.

The case of the disappearing author

The decision of what to keep and what to get rid of is the tough editing work of successful career authors. Less practiced writers often reveal too many aspects of themselves.

While writers strive to express their point of view and creative vision, commercial fiction readers generally do not show up to the party to read about their habits, politics or neuroses. A career author’s goal is to write stories that are as accessible to as wide of an audience as possible. Doing that requires some degree of masking your technique and yourself.

The story is the message; the author is hidden.

The goal of bestselling commercial fiction authors is for readers to be immersed in their world of creation. Like those novelists, you want readers of your book to experience it as if they are living it. Your truth becomes their truth. The story becomes their story, not yours. That’s art.

A creative artist struggles to express a perfect artistic vision unencumbered by their own mortal flaws. Still, even the brilliant da Vinci left his mark: in the painted upper left of St. Jerome is his fingerprint.

Have you ever taken note of TMI in fiction? Was it your writing or someone else’s? Share with us on Facebook.